Visual music: Tocsin

What happens when we 'see' music?

Visual music is a centuries-long tradition in which shapes and colours can represent musical ideas and forms. Personal computers offer new possibilities for expanding this practice, as music can be used to create images and animations in real-time, just as images and animations can be used to create music.

The video I am sharing today, Tocsin, seeks to explore a simple question: can ‘seeing music’ alter how we experience it? For instance, can the eye reveal patterns, structures, or details in the music that the ear might otherwise miss?

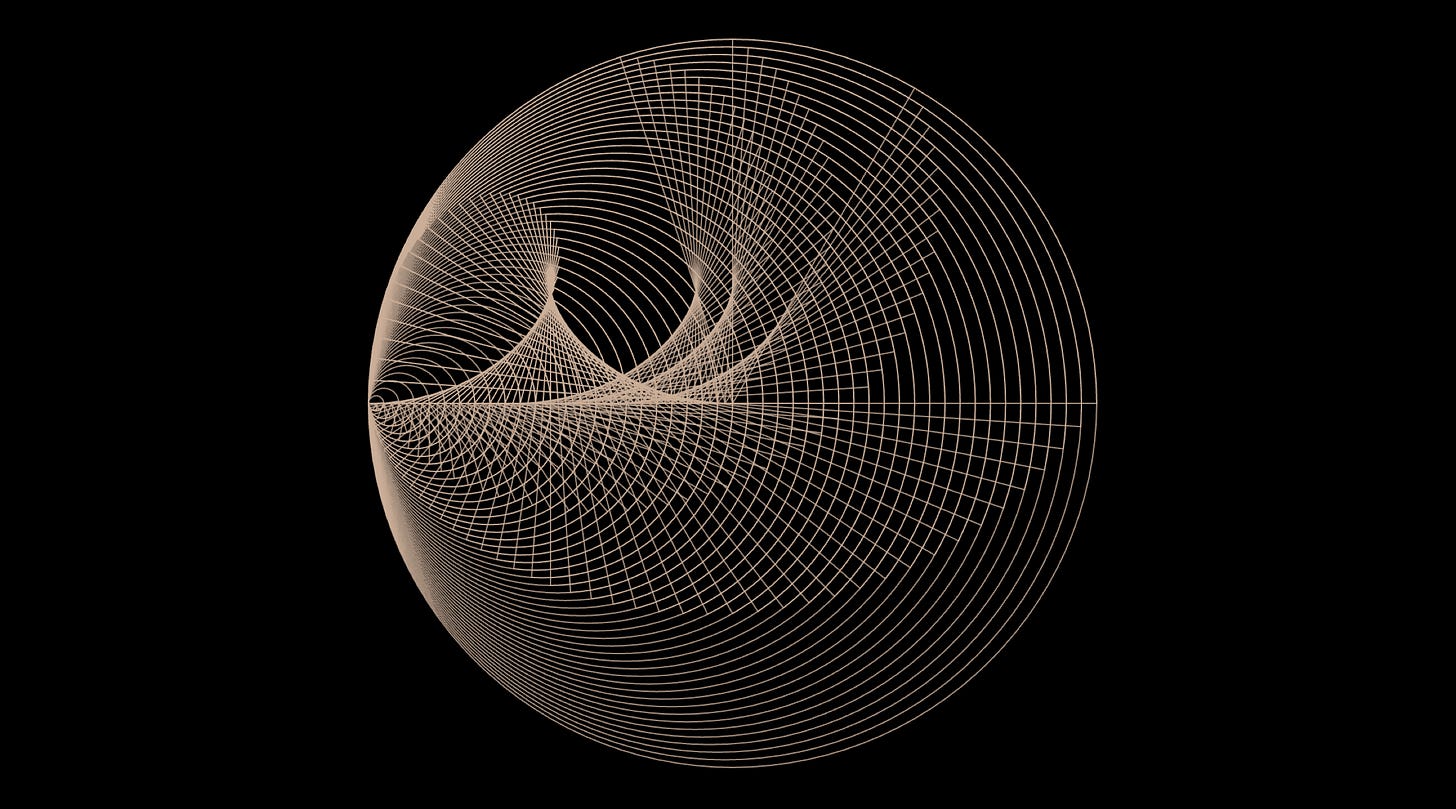

My hope is that by watching the animation, whose movements are conducted entirely by the music, it might provide an intuitive insight into the gradualist development of the composition. I call this gradualist development ‘deep phasing’, and hope that the animation can describe it in a visceral and literal manner, not possible through words.

The composition and animation were created using two open-source programming languages: Supercollider and Processing. A third component, Open Sound Control (OSC), was used to create a bridge that allows these programs to communicate with each other. In my case, Supercollider, the music program, controlled what happened in Processing, the visual program.

For the avoidance of any doubt, none of this involves ‘AI’. I coded everything myself, and the program is using the evolving mathematical structure of the music to shape the visuals. Every movement comes directly from the music, almost as if the music were dancing. I sought feedback and advice from Lucia Molina Pflaum, who helped shape and refine the visual aspect of the project.

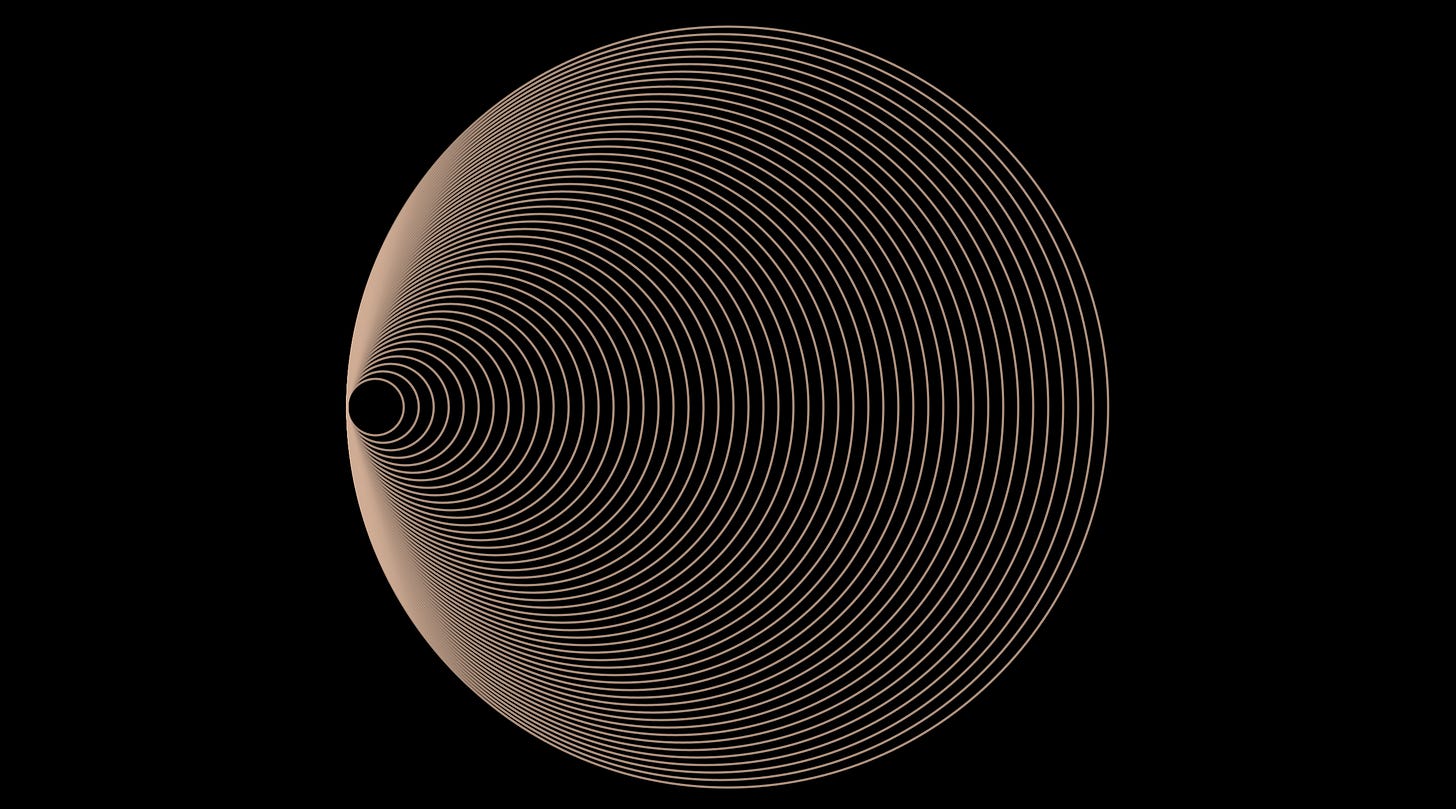

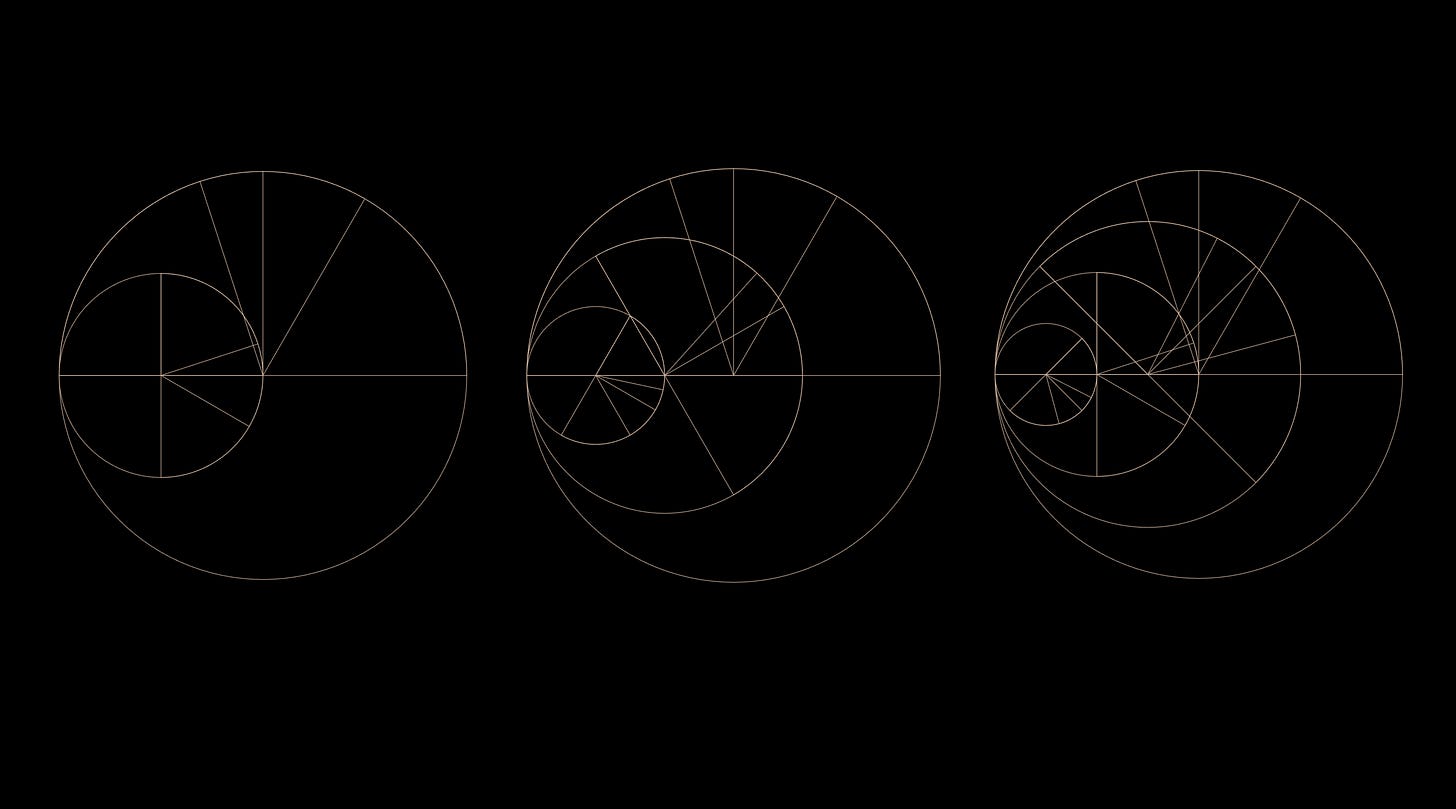

The 48 concentric circles represent the 48 notes from the church bell sample used to create the composition, consisting of a 6-note melody repeated 8 times (6 × 8 = 48). As each successive note is played, the corresponding ring lights up, and a series of rotating lines pass from left to right. The rotating lines represent the swinging of the bells, and the unique relationships of the ever-changing phase patterns they create.

I recently listened to Eight Lines by Steve Reich. I’d heard the composition many times before, but this time it spoke to me anew. My first instinct was to get a copy of the score to help gain a deeper understanding of the music. I wanted to see its 5/4 rhythms written down, jump forwards and backwards across its structures, and know exactly what was happening with the bass clarinets and piccolos.

I am aware that for many non-musicians, this is a mystifying practice. Music is revealed entirely in sound, so why read a score?

Consider the difference between books and audiobooks. Although audiobooks have all the same words as a printed book, listening to an audiobook is a distinctive experience.

With a printed book, one can re-read sentences, leisurely interpret the text, choose a pace and tone of voice, flick through it, feel the weight of the pages and their words in the hand, touch and smell the object, place it on a shelf.

Audiobooks are more ephemeral. There is less imaginative space amid the rhythms, melodies, and cadences of another person’s voice.

Print and audiobooks both have their place, but are different. A music score can bring one closer to the mind of the composer, without the intermediary of the interpreter.

The animation I created is not strictly a score, as there is an artistic dimension to it. However, my hope is that it can provide the same sense of musical insight as a score, while removing the barrier of needing to know how to read music. If given one’s undivided attention, I feel confident the animation can reveal the deep pattern at the heart of deep phasing. After watching it, please do not hesitate to leave a comment, as I am curious to know how people experience it!

Final note: I wanted to share some good news. The British Library’s Sound archive has requested to acquire all of my music to ‘provide the safest possible home… for preservation and access, for many generations to come’ and allow it to remain ‘part of the nation's audio & cultural heritage’. I am delighted the music will have a physical home in London, the city I grew up in and lived most of my life. Thanks again for the support!

Completely fascinating! I saw insect legs rotating across the sphere and emerging again from a ‘hole’! I loved the increasing rhythm and shortening of the pattern. Something reminds me of Gerard Manley Hopkins’s notion of inscape in nature. A novel way of listening for sure

Wasn’t Orpheus supposed to have created things through music?