The creative possibilities of deep phasing

An examination of the emergent patterns that arise from deep-phasing compositions

I want to focus here on deep phasing, a technique I have been using to create a new series of compositions. The compositions are almost complete, and I wanted to give an insight into the techniques used to create them.

What is phasing?

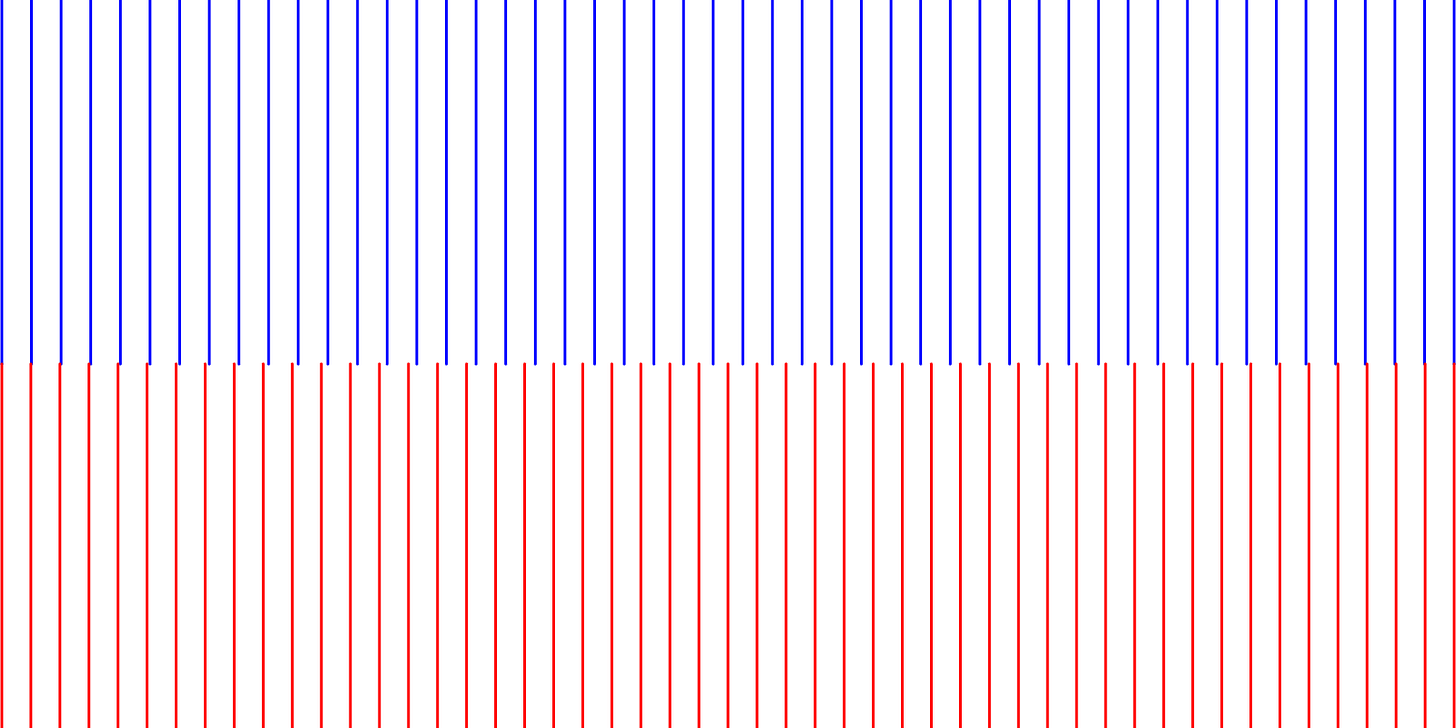

Before describing deep phasing, it helps to be clear about traditional phasing. Phasing, in its simplest form, is a technique in which two voices are repeated at slightly different speeds over the same time period. They start in sync with each other, go out of sync, and then return to being in sync with each other. To understand this better, it helps to visualise this process. The image below represents two voices repeating over a period of time. The red lines represent a voice looping 51 times, while the blue lines represent a voice looping 50 times. They start in sync, the red voice goes faster than the blue voice, and then they finish in sync, creating a very simple phasing pattern.

Phasing is a musical technique developed by the New York composer Steve Reich, who discovered it while experimenting with tape loops in 1965. I wrote an article called Steve Reich’s Exploration of Technology Through Music, in which I described this technique.

In what is now musical folklore, the young composer set up two tape recorders in his home studio with identical recordings he had made of the Pentecostal preacher Brother Walter proclaiming ‘It’s gonna rain’. He pressed play on both machines and to his astonishment found the loops were perfectly synchronised. That initial synchronisation then began to drift as one machine played slightly faster than the other, causing the loops to gradually move out of time, thereby giving rise to a panoply of fascinating acoustic and melodic effects, impossible to anticipate or imagine without the use of a machine. The experiment formed the basis for Reich’s famous composition It’s Gonna Rain and established the technique of phasing.

The following image visualises the phasing pattern for Reich’s It’s Gonna Rain: the top half represents one of the loops, which repeats 392 times. The bottom section represents the second loop which repeats 393 times over the same period of time.

Without accurate machines, this kind of gradual phasing would be impossible since it lies beyond the capability of musicians to reproduce it. However, it is also rooted in instrumental and vocal traditions, such as canons. If you have ever sung a round of ‘Row, row, row your boat, gently down the stream’ in counterpoint with others, then you have a sense of where this music comes from.

What is deep phasing?

Deep phasing is a natural outgrowth of traditional phasing, made possible through the proliferation of certain new digital technologies. Unlike tape machines, which are large, inaccurate, and expensive, modern software is powerful and flexible and opens the door to a world of new creative possibilities.

For instance, one can create multiple ‘tape machines’ in software, opening the possibilities for more complex phasing compositions with far greater numbers of voices. To help imagine this, visualise Steve Reich in a studio with 50 highly accurate tape machines controllable from a single interface!

Nevertheless, this powerful software can also present new problems. For example, the time taken for two loops to go from unison to unison is relatively short: the main phasing section of Steve Reich’s It’s Gonna Rain takes roughly 5 minutes to resolve. However, if you have dozens of loops playing at slightly different speeds, then the time taken for the loops to travel from unison to unison becomes sufficiently long, so much so that nobody would want to listen to it in its entirety.

To make deep phasing engaging, it is necessary to select and shorten passages to a length that is meaningful for listeners. Just as a photographer goes through a process of selection when capturing a landscape or community, so should a composer when working with deep phasing techniques.

Deep phasing composition

This is a composition called Campanology, which was created using deep phasing techniques. It uses a bell-ringing sample taken from a church in Cornwall, South West England. The sample is duplicated 12 times and then looped at slightly different speeds, taking three hours to go from unison to unison. There is a selection process to create the final composition, in this particular case, the last 14 minutes of the cycle, where the phasing resolves and all voices return to unison back, was chosen for its interesting timbre and sense of development.

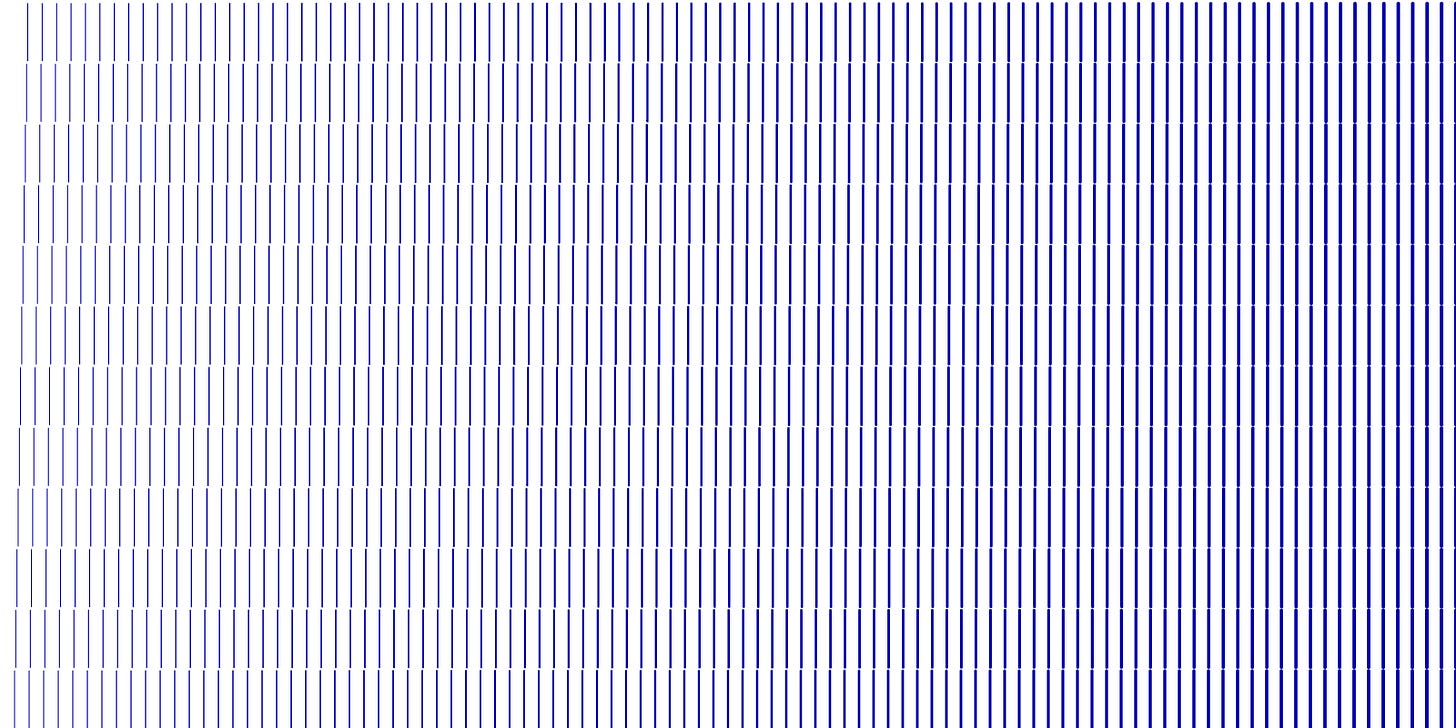

The image below visualises this composition. The 12 rows represent the 12 voices looped - the top row shows the slowest repeating loop, and the bottom row the fastest. Hopefully, It is possible to see that on the far left of the image, the patterns are slightly misaligned and out of sync, only reaching complete alignment and resolution at the far right of the image.

I describe this form of phasing as ‘deep’ due to the length of the cyclical patterns it produces. The term is inspired by the geological concept of deep time, which also requires a mental acclimatisation to much longer time scales. Phasing — as with various other algorithmic techniques — can, at moments, provide insights into nature. Although digital-looking, the image at the top of the article, which visualises the start of a massive 200-voice phasing pattern, unmistakably resembles waves on water, demonstrating that even when engaged in the seemingly artificial world of machines and software, the connections between nature and art majestically reveal themselves.

A theoretical question: Some musicians may wonder while reading this article if there is a fundamental difference between phasing and polyrhythms. After all, if Reich’s composition It’s Gonna Rain features a juxtaposition of 392 loops over 393, is it not simply a 392:393 polyrhythm? Mathematically, yes. It seems there is no distinction between phasing and polyrhythms. However, in practice, musicians will approach them differently, just as audiences will perceive them differently. Accurately discerning the nuances in a 392:393 phase pattern is beyond human perception in a way that does not apply to a 5:6 polyrhythm. Certainly, there will be a hard-to-define liminal space where polyrhythms blend into phasing patterns, but this will primarily be understood through practice, not theorising.

[Edit 17. 06. 2025]

The ideas explored in this article eventually culminated in a record called Toscin, released on Bandcamp. You can listen to it below.

Super interesting. I was wondering if this technique in any way relates to Pauline Oliveros' practice of Deep Listening?

I wonder if non-musician Brian Eno ever experimented with deep phasing. I downloaded his tech app Bloom.