Does the caged cicada sing?

How nature's most boisterous-sounding insects can inspire music.

As summer fades in Spain the sound of cicadas disappears with it — a sound I have only recently begun to listen to attentively. Previously cicadas seemed exotic, and like with all things exotic there is a tendency to let one’s preconceptions obscure a more realistic observation of them. A palm tree to someone who lives in a cold climate may represent a stunning and iconic tree; to someone who lives in a tropical climate they may represent a series of ordinary trees of varying shapes and sizes; to someone who studies palm trees, they are one of over 2500 species — a subject for a lifetime.

Something similar can be said of the sound of cicadas. Cicadas may have a general sound, in the same sense that palm trees have a general look, but with over 3000 species of cicadas, there is diversity in their sound. Just as there is no single bird song — the blackbird, starling, nightingale, and skylark all sound completely different — there is no single cicada song.

Despite this diversity, there is, of course, a generality in their sound. Cicadas emit noise through vibrating membranes near the base of their abdomen. Encyclopaedia Britannica describes three reasons why they do this.

Males of each species typically have three distinct sound responses: a congregational song that is regulated by daily weather fluctuations and by songs produced by other males; a courtship song, usually produced prior to copulation; and a disturbance squawk, produced by individuals captured, held, or disturbed into flight.

Cicadas’ sound often occupies a particularly liminal frequency, where rhythm can accelerate into tone and tone can decelerate into rhythm. As with all things in nature, there are no straight lines, and both the pitch of cicadas and the rhythm of their pulses fluctuate, governed partly by heat. Their congregational song has a sense of togetherness but without the unifying singular tempo of most human music.

To hear cicadas is to hear noise, but to listen to cicadas reveals something more profound. They do not possess the melodic virtuosity of the blackbird, but they can generate rich columns of harmony and complex overlapping rhythmic phasing. A tantalising passage from Encyclopaedia Britannic left me wondering about what beautiful sounds I might yet discover.

The cicada appears in the mythology, literature, and music of many cultures, including those of some Indigenous peoples in the Americas, and the males of certain Asian species have even been kept in cages for their melodious songs.

The slow modulations of the cicadas reminded me of a composition by the late Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho, Vers le blanc. It is a slow, simple, and process-driven piece of music that felt relevant to the congregational song of the cicadas. To listen to her piece without restlessness requires a change of expectations and a willingness to enter into its very particular sense of time, much like when listening relaxedly to the sounds of the natural world.

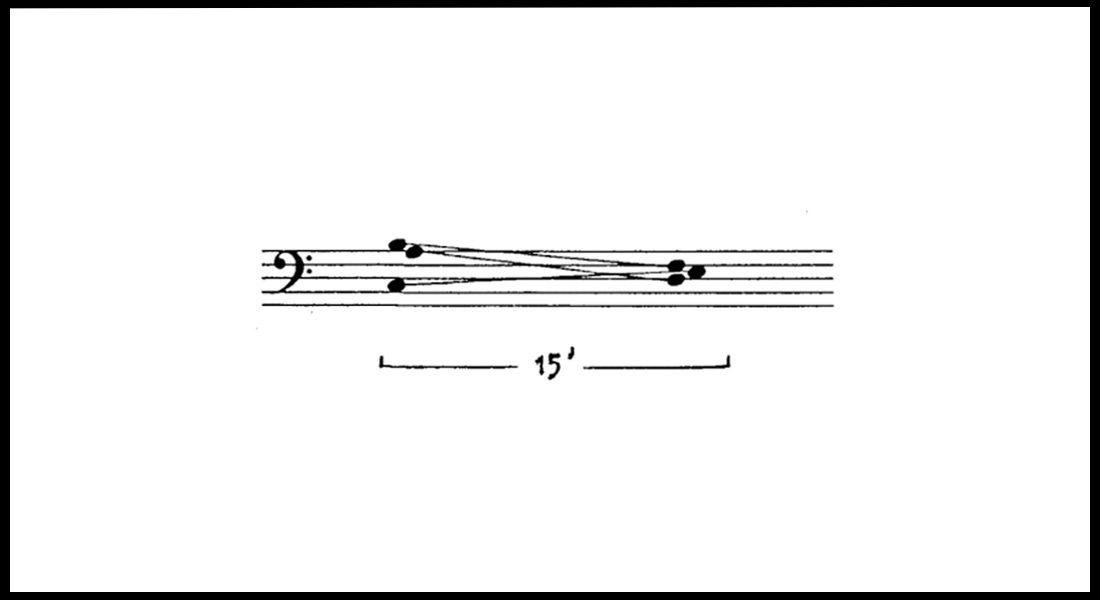

You do not have to be a trained musician to understand Kaija Saariaho’s miniature score for Vers le blanc. It shows one note cluster modulating to another (ABC → DEF) by glissando (a pitch slide) over 15 minutes. As the slanting glissando lines on the score show, the two top notes (A & B) descend in pitch while the bottom note (C) ascends. The piece was performed in 1982 at the Darmstadt International Summer Courses, as well as a handful of other concerts. She used early computer voices to create the piece, as it required meticulous precision to achieve the gradual and continuous pitch modulation that tests the limits of our perception. She never released a recording, so unless you attended a rare performance, it leaves you imagining.

Her composition raises the question, to what extent can we sense a change happening slower than our ordinary perception? Such as, to what extent can we sense the turning of the planet through the changes of light in the day? While the cicadas operate within the realms of ordinary perception, is their song not also comprised of similarly subtle modulations that gradually transform sound states?

With these ideas in mind, during the intense summer heat, I wrote a composition inspired by both cicadas and Kaija Saariaho's composition. However, rather than focus purely on a shift of pitch, I was curious to experience a gradual shift in position too. This is called musical spatialisation — a somewhat tautological (but necessary) term for the positioning of sounds in space. It is tautological because sounds, like objects, can only ever exist in space.

I wanted the spatial shift of sounds to be slow but perceptible. A shift from left to right then right to left. I made a patch with the music programming language Supercollider and used sine waves — the simplest waveform possible — as a sound source. As the sound makes this journey through space its pitch also gradually ascends, then drops rapidly when it reaches its destination. The sound itself does not resemble that of the cicadas’ but the pulsing does. If you listen with stereo speakers the sound travels from one speaker to the other, If you listen with headphones the sound feels like it travels through your head.

If one expects to hear the melodic qualities of a blackbird then this composition might disappoint, however, if one treats the composition as if one were surrounded by the congregational song of cicadas, then something interesting might emerge.

Cicada I

Cicada II

I have unsuccessfully searched the Internet for audio of actual caged cicadas with melodic talent. Despite finding nothing yet, I will keep trying. I did, however, come across this interesting article in the New York Times, which describes and provides audio for some interesting cicada sounds. If you have heard melodic cicadas please feel free to share your experience in the comments.

Cicada song always makes me think of the southern States, where I have heard them most. We named a song after them, once, when the stacked 's' sounds of a repeated sampled phrase took on that choral feel you speak of.

We share a fascination with the singing of cicadas, I see. I'm sure we're not alone. The ones I've been listening to most of my life have been the Texas variety, although I've heard them in other places as well. I regularly reference them in my poems, including several included in my Substack. As usual, you've widened my window on the world with your post--or should I say my listening chamber?