On June 13th, 1940, less than a year after the United Kingdom declared war on Hitler’s Germany, an order was sent that all church bells should be silenced, except in the case of an air raid. Following this decree, thousands of bells towers across the country fell silent, reserved for use as warning systems to alert citizens of a Nazi invasion. In such an event, the bell towers would sound simultaneously, creating a clangerous cacophony to warn and summon. While pragmatic, it was also deeply symbolic.

"On June 13th 1940 The order was given out on the wireless that Church and Chapel bells must not be rung except for air raids."

The silencing of the United Kingdom’s bells from 1940 to 1943 broke normality. Faced with an uncertain future, there was no guarantee they would ever ring again. Their silence was a freedom already lost. The tense quiet that followed a reminder of the possibility of far greater losses to come. At any moment, were they to sound, it would be a call to possibly the final fight for freedom.

As someone who deliberately chose to live beside a bell tower, I find it hard to conceive of it being silenced. The sound of the bells connects one to something ancient, reassuring, and communal, as they mark and express time, festivity, and ritual. Every day, one is subtly shaped by their melodies and timbres. Just as a musician tunes the strings of their instrument, a bell tower tunes its community.

The silencing of England’s bell towers not only ruptured the comforting communal expressions of time, but also a fascinating centuries-old artistic practice called change ringing — an art form where a set of at least three musically tuned bells are rung in many different orders to create a continuous cascade of subtly changing melodies. Of the approximately 6100 change-ringing bell towers in the world, 5700 are in England. An unexpected offshoot of the development of mechanical time, they went beyond marking time and opened the door to computed music.

Change ringing compositions are created using methods, which are algorithms that change the order in which bells are played, thereby allowing for the generation and exploration of countless melodic permutations. Centuries before Ida Lovelace had speculated about music software or Alan Turing had contemplated whether computers could think, music was being computed by bell ringers in church towers using only their instruments, minds, and bodies to process complex patterns.

The following is an example of a method which rings all six possible permutations for three bells. When all possible permutations are played this is called a peal. In the notation, each bell is represented by a number in the sequence, played from left to right.

> 1 2 3

> 1 3 2

> 3 1 2

> 3 2 1

> 2 3 1

> 2 1 3

> 1 2 3

In the first change, the order of the last two bells is swapped (123 → 132). In the second change, the order of the first two bells is swapped (132 → 312). This formula continues until, after six changes, the peal is complete, and the bells return to their original order (123).

Towers with more bells, while rooted in fundamentally similar swapping methods, require more complex methods to create a peal. Ingenious methods exist that allow for every permutation to be played without repeating any. Ringing a peal can last for hours, or even days, since with each additional bell, the potential permutations increase exponentially.

The formula for calculating the number of permutations for a given bell set is quite simple:

3 bells = 1 x 2 x 3 = 6 permutations

4 bells = 1 x 2 x 3 x 4 = 24 permutations

5 bells = 1 x 2 x 3 x 4 x 5 = 120 permutations

6 bells = 1 x 2 x 3 x 4 x 5 x 6 = 720 permutations

7 bells = 1 x 2 x 3 x 4 x 5 x 6 x 7 = 5040 permutations

8 bells = 1 x 2 x 3 x 4 x 5 x 6 x 7 x 8 = 40320 permutations

It is not long before the number reaches staggering levels. For instance, St Paul’s Cathedral in London is home to 12 change-ringing bells, allowing for almost half a billion permutations!

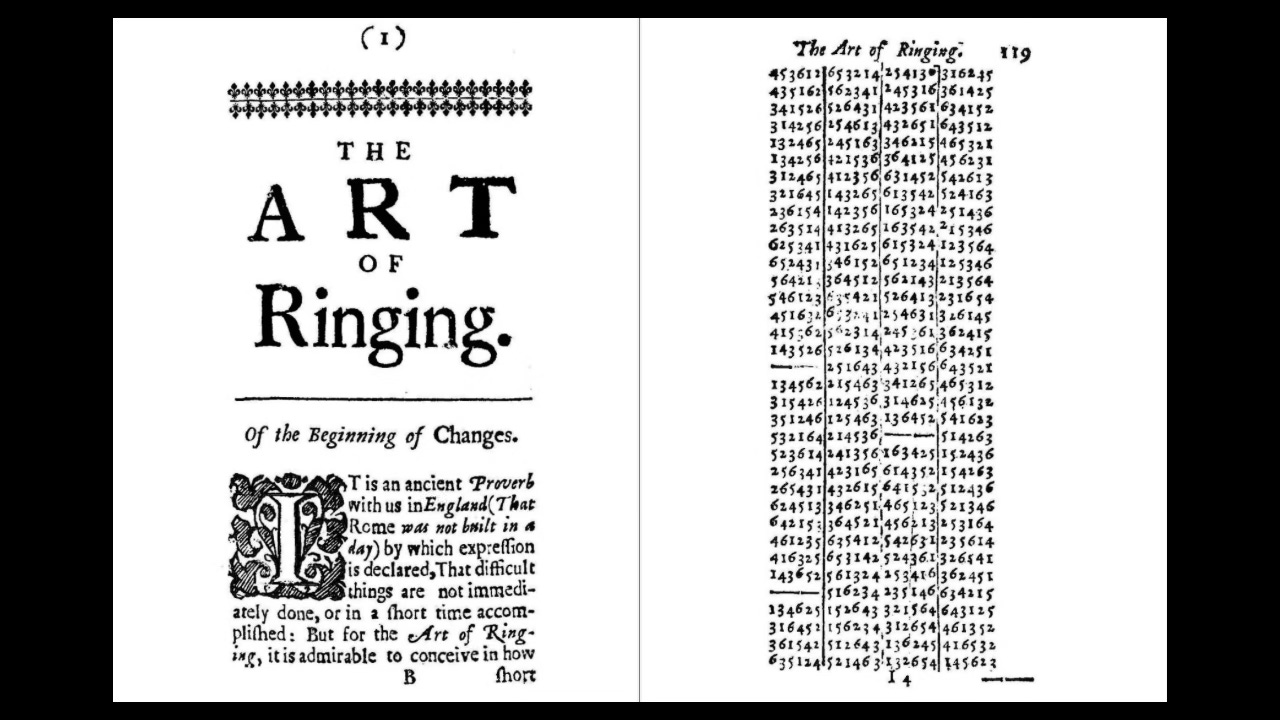

To get an insight into the inner workings of such music, you can examine compositions, like the one above, in the 1668 book Tintinnalogia: the art of ringing, which reveals just how closely the architecture of the music resembles modern computing. The compositions look like arrays of data, which were processed by human bell ringers, who output sound through bells while storing the memory of these compositions in the minds of the people who practice the art form and the books they wrote. These bell towers were essentially early musical computers.

Far from music written traditionally by a composer, they use impersonal processes to reveal the nature of an unfolding algorithm. The result is a continuous cascade of sound, distinct from the traditional narrative form of a song or symphony. Perhaps the reason this music has been permitted for centuries to ring loudly throughout villages, towns, and cities across England without much protest is that it resembles a natural process.

During the Second World War, the Nazis confiscated over 175,000 bells from towers across the continent to melt and produce weapons. A similar mass destruction of bells occurred during the First World War. The irony of melting these beautiful objects and converting them into objects of war not being lost Deacon Karl Munzinger of the parish of Kusel in southwestern Germany, who, in his sermon on July 22, 1917, had the following to say about converting these instruments into weapons of war.

They will speak a different language in the future… It goes against any feelings that they, who like no other, preach peace and should heal wounded hearts, should tear apart bodies in gruesome murders and open wounds that will never heal.

Having drawn inspiration from this art form for two decades, I felt the desire this year to add my own interpretation to it, and as a result, I have written two compositions inspired by change ringing, one of which I am sharing today. Like change ringing, the music is composed using a process. Aesthetically, the music shares more in common with watching a sunset than reading a novel. There is no great drama or plot but a gradually deepening transformation where small details subtly and constantly change from one moment to another.

History reveals these beautiful musical vessels to be the confluence of the finest artistic, scientific, religious, and engineering ideas. While strictly speaking, they are religious objects, they also owe their existence to secular achievements and, therefore, in my view, belong to all of society. Their effect on soundscapes permeates both rural and urban living and is at once technical and emotional, historic and contemporary, spiritual and material. In the same way that their silencing signified freedoms lost, their ringing signified the endurance of freedoms defended. Freedoms that should not be taken for granted.

Campanology

Beautiful article. One of the most interesting music/math topics ever. I am still mystified by how the ringers keep track of the patterns completely in their heads!

I'm also gonna need to know more about this statement: "as someone who deliberately chose to live beside a bell tower" !!!!

You've also got me thinking about the silent 'peals' of Push, Press, Roll-Back and Ward-Off in T'ai Chi pushing hands, the way they cascade in this rhythm until interrupted by a 'change'.