Open Studio: a cyclical vision of rhythm

Visual patterns that can change how we imagine music

I have always been interested in the sketches and colour tests that surround the canvasses of paintings, as they provide insights into the artist’s process. So in the same spirit, here I wish to share experiments, ideas, and techniques that help inspire my work, and often take me in unexpected directions. I invite you to my studio in Valencia, Spain, to share sketches and studies that I hope may inspire you too. I call this Open Studio.

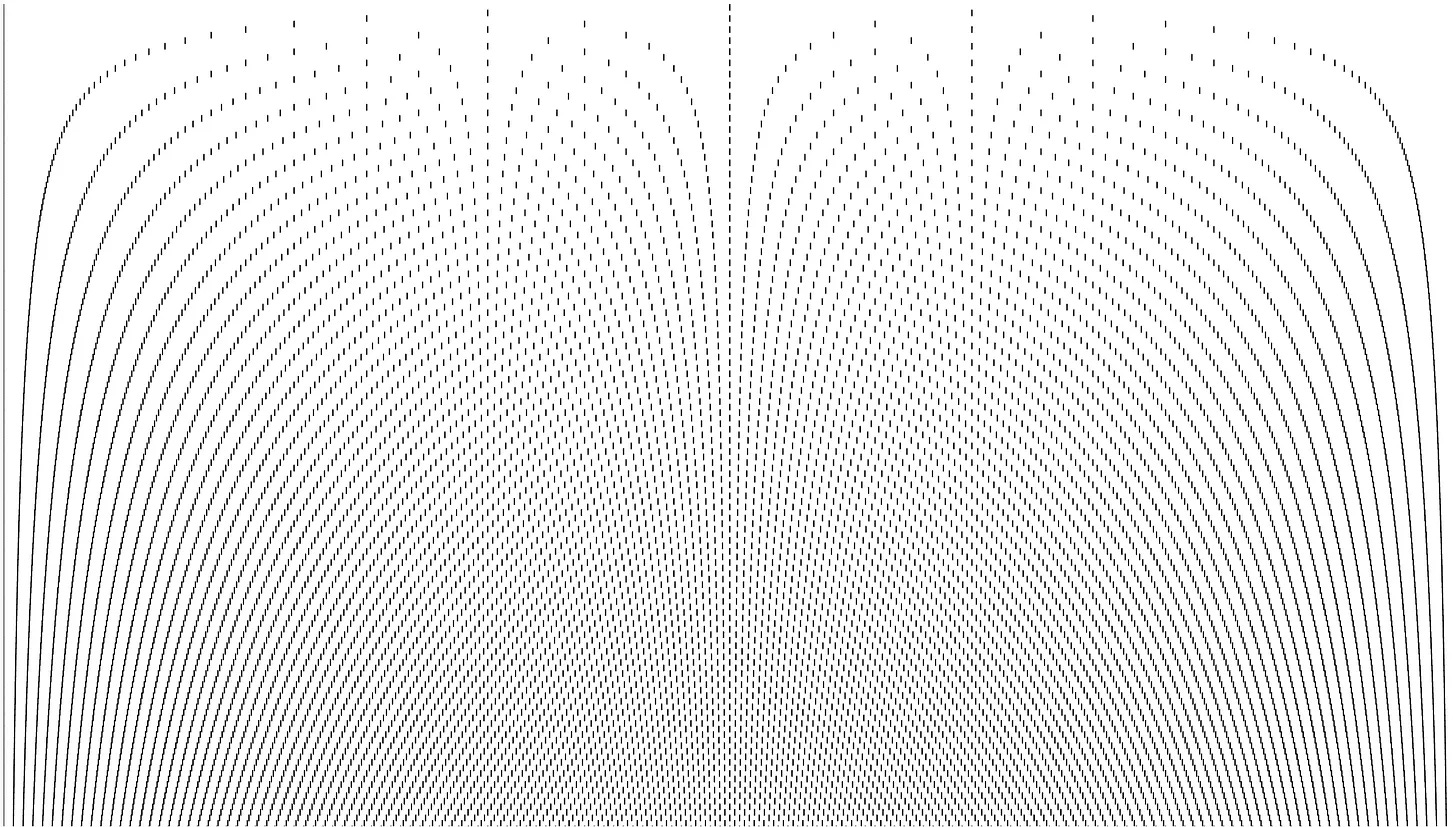

About this time last spring, I shared some visualisations of giant polyrhythms in a post called Have you ever wondered what rhythm looked like? I created them in a program called P5JS, using a simple algorithm. The results surprised me, as despite having studied percussion since childhood, I had never anticipated rhythms looking the way they did.

Here is one example.

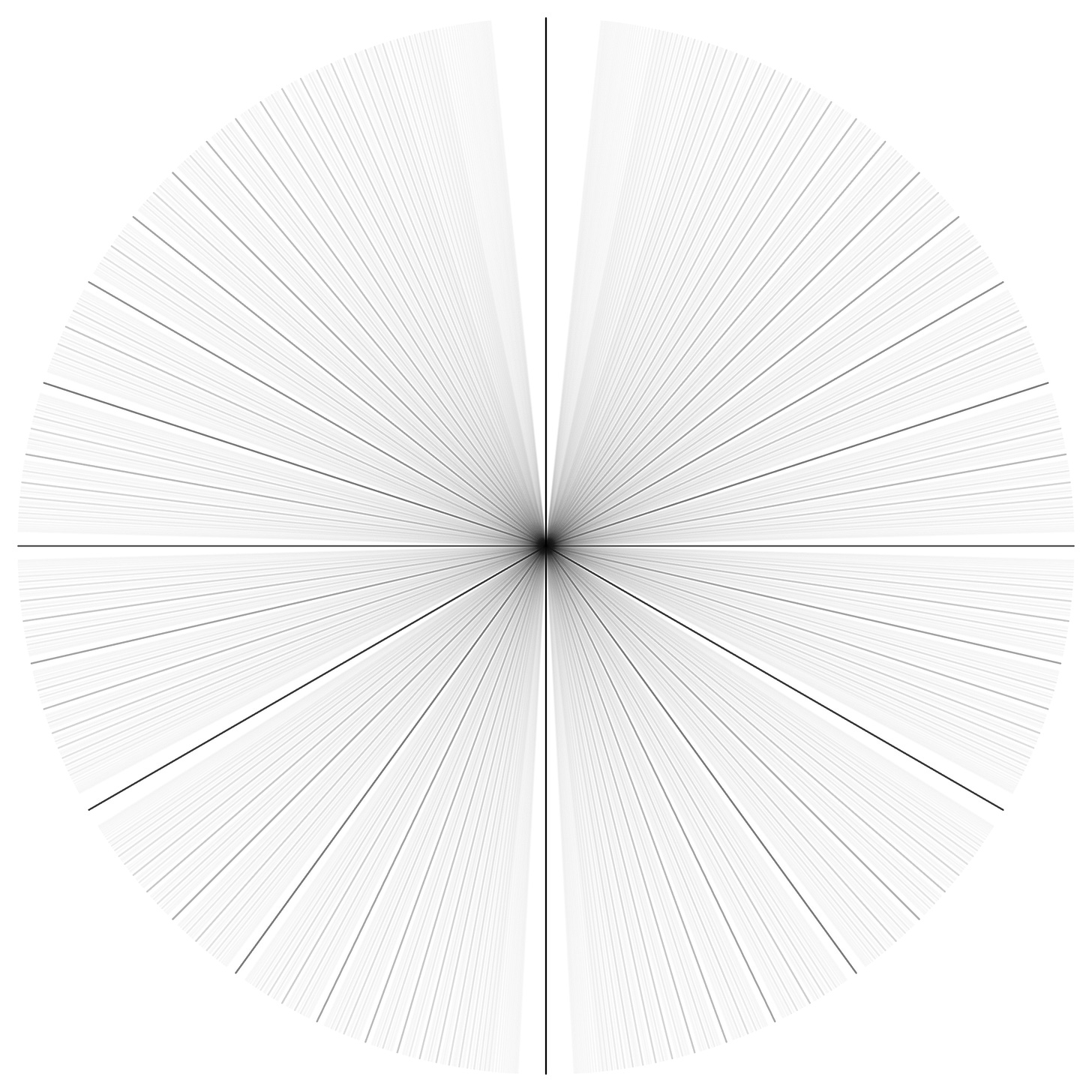

Last Christmas, while taking a break, a new idea entered my mind for how the same rhythms could be visualised differently. Rather than having the rhythms travel from left to right, or right to left - as they do in the image above - they could rotate around a centre point.

The rhythms would be visualised cyclically.

When I ran the code in P5JS I was astonished. The image it returned was beyond any conception of what I thought rhythm might look like. It looked organic, even botanical. It appeared soft, majestic, and elegant, while also rigorous, symmetrical, and detailed.

The process for generating the image was simple.

Draw one radial line at 0°. Then add two lines equidistant in rotation. Then add three lines equidistant in rotation. Then add four lines, and so on.

You can see it develop here.

The original images inspired my album The Code; the latter rotational image I used as the pattern for its artwork. Both influenced my thinking.

Visual arts are powerful because they can be perceived instantly, whereas music, as with film and literature, unfolds over time; the image acts as a cartographer, mapping out time’s contours and revealing patterns that provide clues to music’s deeper nature — concepts that are difficult, if not impossible, to perceive within time’s flow.

I should point out, that the pattern I have shared today describes music that is impossible for human performance. Beyond the first few permutations, the rhythms become too challenging for human players. The same is true for the more complex visual images, which contain thousands of lines at precise angles and shadings that would be too difficult for the human hand to draw accurately.

The visual artist Vera Molnar — whom I previously quoted in the Liner Notes, but who sadly has died since then — was insightful about such uses of computers in art.

Without the aid of a computer, it would not be possible to materialize quite so faithfully an image that previously existed only in the artist’s mind. This may sound paradoxical, but the machine, which is thought to be cold and inhuman, can help to realize what is most subjective, unattainable, and profound in a human being.

There are two striking ideas in this passage.

The first is Molnar’s emphasis on the centrality of the human mind, which she locates as the source of inspiration: the machine materialising an image that ‘previously existed only in the artist’s mind’. It is a traditional approach to art, where the computer as a tool channels artistic inspiration.

The second idea, that machines can realise the ‘unattainable’, is more radical. The machine, rather than being clumsy and mechanistic, can help create subtle and profound art. Its speed and precision facilitate new forms and ideas.

One could go further, and propose that machines bring us closer to metaphysical ideas — by which I mean platonic, idealised forms. For example, a perfect circle is impossible to create with the human hand, due to its inaccuracies, and while machine renderings of circles are strictly inaccurate too — whether in pixels or printed form — they are nevertheless much more accurate than handmade renditions.

This is not to suggest that machine-created art is superior to handmade art, it is simply different. For instance, an artist like Michael Armitage, who paints with oil onto Lubugo bark cloth, creates art that a machine cannot — his materials, ideas, and techniques are unique. By contrast, an artist like Vera Molnar who created computer art through generative processes, expressed her way of perceiving the world through an entirely different medium. Both artists’ approaches are distinct but valid.

The polyrhythms images in this post have something of an unattainable or metaphysical quality, in that they are impossible for either musicians or artists to render accurately. Yet, despite being beyond the capabilities of the human body, their meaning relies on them being perceived. Whether the images are treated as objects of contemplation that are beautiful in themselves, or used as functional tools to help orientate and navigate vast polyrhythms, they require human interaction to be meaningful.

The Code is an example of music that is visually inspired, expressing the intricate geometry of vast polyrhythms. While creating it I sensed that these patterns were just fragments of something illimitable, and began to imagine more powerful tools to explore it. Such tools would unite visuals and music in real-time, bringing the eyes and ears into union and helping with the emergence of a new visual-musical language — a language built using machines, but created for people.

Listen to the album The Code which was inspired by the images and ideas explored in this post.

Update / 25 April 2024

In the comment section for this post Su Terry suggested using the Fibonacci sequence. It struck me as a good idea, and the result turned out to be intriguing so I have added it to the post.

The image uses the first 15 numbers of the Fibonacci sequence. There is a pattern, though it is less regular and harder to discern than the patterns generated from the previous method.

Since the Fibonacci sequence is exponential, it does not take long before the whole circle turns black, as thousands of lines are layered on top of each other. Therefore, the method only really works when there are fewer than 20 iterations.

Thanks for the good suggestion Su!

I am reading Alphabet, a book of poetry by Inger Christensen where she used the Fibonacci series to generate the structure of the verses. I wonder if this could somehow be done with sounds/rhythms.

I love the visuals that you generated from the polyrhythms. And you raise some interesting questions around the musical capability of machines in an effort toward “perfection.” I work with sound and so often am trying to get the digital stuff to perform less “perfectly,” more analog, but for sure you have a point that (so) many things are beyond human performance capability, and in this respect we have a lot to learn. Anyway, thanks for the words and great images.