A visionary who predicted the powerful influence of Indian music on the West

The Irish prodigy violinist Maud MacCarthy travelled to India to learn new musical ideas in an immersive and radical way

At the start of the 20-century a visionary musician quietly changed music, and then disappeared into obscurity. Despite having been sought out in her day by composers such as Edward Elgar, Gustav Holst, and John Foulds, she was until recently almost entirely forgotten. Yet her philosophy embodied new ways of thinking about music that went beyond of the ethnocentrism of her age. To exclude her from history means to offer an incomplete and sanitised version of it. Her story matters, as it helps us understand how modern music was arrived at, and where it might be heading.

Born in Ireland in 1882, Maud MacCarthy was a musical prodigy who combined a respect and mastery of tradition with a counterculturalism that fused music, spirituality, and an almost utopian globalism that somewhat predicted the hippy spirit of the 1960-70s. Some of her achievements include creating a form of music therapy long before it was considered a legitimate practice (she named them ‘sound baths’), predicting that geographically distant musical traditions would significantly influence each other in such a way as to produce radically new music, and developing an idiosyncratic worldview that transcended the sense of cultural superiority that permeated the British Raj.

MacCarthy spent her early childhood in Australia, which possibly aided her later in life to adapt to living in different countries and continents. At a young age she developed into a brilliant violinist, studying at the Royal College of Music, London, and touring internationally. However her life changed dramatically when in her early twenties an injury ended her performing career; rather than retire from music she travelled alone to India and turned her mind to studying the vast Indian classical music tradition.

Few instruments could have better prepared her for this than the violin, already in common use in South India, though played with a significantly different style and technique. The intonational sensitivity required of string players provided her with the skills to accurately perceive gamakas, the subtle and idiosyncratic melodic ornamentations of Indian classical music. She described this dimension of the music as ‘microtonality’, and though she probably did not literally invent this term as has been claimed, her use of this new terminology indicates a modern manner of thinking.

MacCarthy’s personality truly comes to life in her own words, filled as they are with a passionate and youthful excitement, delivered with the rhythms and cadences of musical passages. For example, when describing her time in India she reveals a poetic side, recounting an immersion in a culture she clearly loved.

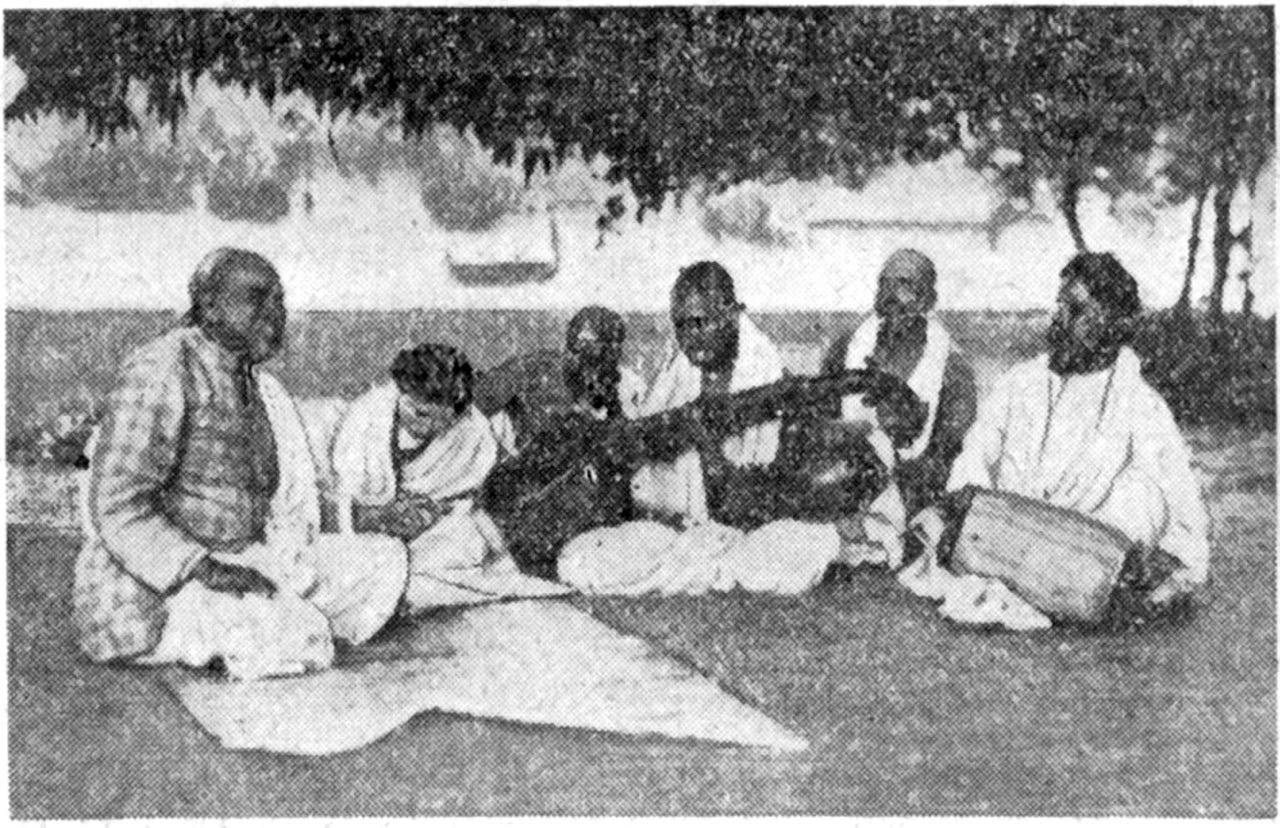

I have hung about the gates of the Central Hindu College in Benares listening to old men who used to sing in a niche in the wall — I have lain awake at night listening to the people coming home singing from the temples, in Madras and elsewhere, or drumming in the bazaars. I have attended concerts, listened to water-carriers, boatmen, women grinding wheat, or gardening fruit from monkeys — I have listened to wood-carriers on the hills and urchins in the towns. Indian friends used to bring musicians to me so that I might note and compare the different styles, and ask questions.

She describes a form of immersive learning where music and culture are inseparable, in contrast to the customary approach of the time which divided them.

During her travels MacCarthy moved around both in the north and south of India — homes to the Hindustani and Carnatic traditions, which in combination comprise Indian classical music. She studied in the traditional manner, taking lessons from gurus, using Indian-language terminology, and learning tabla drums and how to sing. After nearly two years MacCarthy returned to England with the prestigious endorsement of the renowned composer and singer Rabindranath Tagore, who described her as ‘eminently fitted to introduce Indian music to a Western audience.’

Upon her return rather than publishing a book, as might be expected, MacCarthy took to giving public lectures on Indian music, and attracted large crowds that often included some of the most esteemed musicians and composers of her day. She brought the music to life through her voice and tabla in a manner true to the primarily aural tradition she was representing, and even described the notation of Indian music as a mostly ‘fruitless task’, aware that by doing so — regardless of intent — meant shoehorning the music into a more Western form. Despite this she intended eventually to write a book on the subject, though unfortunately never did.

Thankfully some of her original thinking remains in the form of written lectures. In one delivered to the Theosophy society, of which she was a member in her younger years, MacCarthy describes with rare honesty both Indian and Western classical music as being incomplete, going on to expound a vision of global music that would not just influence the world artistically, but also socio-politically.

To help make sense of the following quote, broadly speaking rāga refers to the pitch or melodic dimension of Indian classical music, and tāla to the temporal or rhythmic.

Rāga and tāla are also by no means complete forms of musical expression. In all modern musical creations of any importance there is, however, a tendency towards change and exchange: change of subject and of materials and methods; and exchange of ideas and of theories between cultures hitherto considered irreconcilable. Thus, under the impetus of common ideals, the boundaries of nations (and, slowly, of races) are being overpassed; and it seems as if in the blending of East and West, ancient and modern, esoteric and exoteric, and in the flights of imagination which result therefrom, we could already hear the first faint notes promising the music of a glad new day.

MacCarthy even went as far as to describe the character of the person who might create this ‘music of a glad new day’.

…that artist alone is truly great who can submit himself to the preparatory labour which such an ideal must impose, let us remind ourselves that it is in the patient study of, and sympathy with, the little things in the arts of many nations, that we that will acquire the power whereby to strike fresh chords and free new melodies in the music of the future.

Lastly, she outlines her belief that the further development of Western music would require the influence of ideas from the Indian classical tradition.

The principles of rāga—and also, as we shall see, of tāla—may indeed be the ‘missing links’ for which we have been searching in the latest developments of programme-music,—and searching, as yet, largely in vain. To my mind, at least, rāga and tāla have the very spirit and power of ‘programme’ in them, for they produce the atmosphere which is sought for, but usually lacking, in the quite modern Western programme-music. I have heard a well-played rāga produce, with exquisite economy of material and means, results to which many a tone-poem, with all the elaboration of modern harmony and of the modern band, can scarcely attain.

This prediction was accurate. Many composers and musicians went on to seriously study rāga and tāla, and in doing so expanded the spectrum of musical possibilities in Western music. Compositions such as Philip Glass’s Music in Fifths are hard to imagine without such an influence.

MacCarthy delivered her somewhat utopian lecture in 1913, filled as it was with hopeful visions of a borderless world and inspiring predictions about the arrival of ‘the first faint notes promising the music of a glad new day’. Yet a year later the First World War broke out across Europe as millions were killed in the name of nationalism. Whether she foresaw this deadly event or not, it is clear she neither lost faith in her beliefs, nor ignored the horror of what had transpired.

In 1918 MacCarthy left her husband, William Mann, and began living with the English composer John Foulds, who offered her the opportunity of a musical outlet for her ideas in the notoriously male-dominated profession of composition. The couple began collaborating on a large piece, A World Requiem, dedicated to those killed in the recent war. Foulds composed the music and MacCarthy wrote an ecumenical text combining elements from both Christian and Hindu faiths. Together they started the long-standing British tradition of Armistice Day Remembrance, with this giant work for 1250 musicians. The composition was performed for four consecutive years starting in 1923.

Yet in general, Foulds struggled to gain acceptance and success in Britain. As a Northerner and self-taught composer he would have had the rigid British class system working against him, coupled with the fact that he and MacCarthy had lived together unmarried for many years. The BBC barely broadcast Foulds’s most accomplished works, for which he expressed his bitter frustration in correspondence with the organisation.

…while my principle serious works have received the approval of some of the greatest names in the musical world, and also of practical conductors, it would appear, judging from past experience, that a serious work of mine has a poor chance of winning the approval of the BBC Selection Committee.

In Nadlini Ghuman’s excellent book Resonances of the Raj — which I reviewed in my previous post — she meticulously documents the condescension directed at Foulds, which circulated in internal memos at the BBC. To pick one from many examples his music was described as ‘very dull stuff, and the more serious it is the duller it becomes’.

It takes no great stretch of the imagination to understand why almost a decade after the premier of A World Requiem, Foulds and MacCarthy decided to leave behind the ‘austere, colourless London of the 1930s’ and set sail for India to try their chances in a new country and continent. While on international waters Foulds used the transcriptions of Indian compositions from MacCarthy’s youth to compose a five-part orchestral Indian Suite that was completed before their arrival. The mood of the suite, and particularly its final movement, speak of people embarking on an artistic and personal adventure.

Foulds found some initial success in India; he founded an Indo-European music ensemble and was appointed Director of European Music at All India Radio in Delhi. Yet his ambitions to learn first-hand about Indian music were cut short, as in 1939 only a few years after arriving in India, he tragically died from cholera in Calcutta. Much of his music from this time was subsequently lost as the world erupted into the chaos of another war.

After his death his music sunk into the shadows for decades, only being brought back to life in recent years with new performances and recordings of his works and a re-evaluation of his contribution to 20-century British music. The remainder of MacCarthy’s life was devoted to spirituality, with her founding an ashram, publishing poetry under the name Tandra Devi, and writing an autobiography. She died on the Isle of Man in 1967, old enough to see her ideas begin to enter into the mainstream.

At this point one may ask: did MacCarthy and Foulds collaborations represent ‘the music of the future’ that the young MacCarthy lectured about? Did it contain the ‘fresh chords and free new melodies’ of the great artist she referred to?

There are no simple answers to these questions.

On the one hand Foulds and MacCarthy skilfully incorporated many new ideas into their music, such as Indian mēlakarthas (scales), 22-note tunings, and transcriptions of Indian melodies from folk and classical traditions. In particular Foulds’s piano music Seven Essays in the Modes demonstrates a unique approach to music at that point. However, the music the couple created was still fundamentally woven into the existing Western classical tradition without any great rupture to its fundamental fabric. They were planting seeds, but they did not yet represent the dramatic transformations observed elsewhere in the world at a similar time.

In Austria Arnold Schönberg had scandalised audiences by radically destabilising harmony. In France Olivier Messiaen had studiously incorporated birdsong allowing for a figurative dimension to an art form often considered inherently abstract. In the United States Charles Ives had brought about a kind of controlled cacophony through experiments in polytonality. In Switzerland Igor Stravinsky’s had composed The Rite of Spring composing unsettling rhythms that appeared to defy pattern.

These were changes that could be felt viscerally and instantaneously in a way that was not so obviously the case with Foulds’s music, but with a significant difference: the changes by the other composers occurred fundamentally within the culture and grammar of the existing Western tradition, whereas Foulds and MacCarthy’s ambition was to build bridges between distant cultures and transform music globally, allowing cultures to change in many directions.

Foulds’s decisions to break away from the rigid class system of Imperial Britain and enter into a self-imposed exile in India was artistically radical, as were his efforts to develop an all-Indian music ensemble to compose for. It seems possible during this time he could have deeply altered the fabric of Western classical music in ways similar to how his peers had, or a very least been gathering pace to do so, but since most of his music from this period was lost, we will probably never know.

Regardless of how one perceives what was achieved in Foulds and MacCarthy’s music, the couple had unquestionably made the generous effort to open the door to a new approach to music where ideas, rather than geography, took on primary importance. MacCarthy’s youthful predictions were accurate, her influence on her peers profound, and the idea that we might ‘hear the first faint notes promising the music of a glad new day’ ultimately vindicated.

That vindication came in the form of a deep and lasting transformation of Western classical music from influences outside of Europe and North America, changes that challenged Western music aesthetically and philosophically. It is another story, comprised of a different cast of characters, which will be the subject of another essay that I will soon publish. In the meantime I will leave you with some words spoken by John Foulds while on the radio in India, followed by what I consider one of his most interesting compositions.

And the longer I study, the more deeply am I convinced of one thing: that the great gulf which many people imagine to exist between Eastern and Western music is not a reality… Real music is not national — not even International — but supranational. I believe that the power of music to heal, to soothe, to stimulate and to recreate is just the same in Timbuctoo as in Kamchatka, and was the same in the time of Orpheus as it is today.

You can read Maud MacCarthy in her own words in a 1912 lecture titled Some Indian conceptions of music